SLFNHA is excited to celebrate National Indigenous History Month. In honour of this regions rich Indigenous history, we are shining a light on the history makers from in Northwestern Ontario. Enjoy the stories on each of these trailblazing Indigenous History Makers.

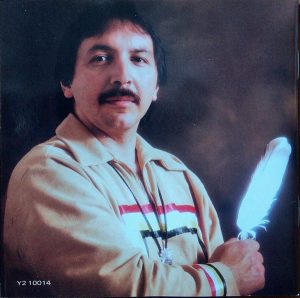

Lawrence Martin

Lawrence Martin was born in Moose Factory, Ontario. He came to Sioux Lookout, Ontario in 1986 where he helped start Wawatay Radio Network and Television. During this time he also became Ontario’s first Indigenous mayor when he won the Sioux Lookout Municipal Election in 1991. He is currently the Manager of Feasibility Study for the Mushkegowuk Council. He spoke with Reece Van Breda, SLFNHA’s Communications Officer, about his accomplishments.

You were Sioux Lookout’s first and only Indigenous Mayor (1991-1994) and first Indigenous person in Ontario ever elected as mayor; What led you to run for Mayor? What was it like running as an Indigenous candidate at the time?

Garnet Angeconeb, at the time, was a councillor leading up to the election in 1991 and he was encouraging Indigenous persons to run for council. After meeting at the friendship centre, we decided to form a task team for running for mayor and I decided to put my name down.

It was fun to campaign, to run and speak to people. We had a live debate, and it was broadcasted over Wawatay Radio for the first time ever.

The night they were counting the ballots, hanging around the area I could hear my name being called, and I could feel the energy and sure enough I won. It was a great feeling, people putting their trust in me.

What are some achievements that you are most proud of during your time in Sioux Lookout?

The sewer and water treatment plant – my claim to fame! I went all the way to Queen’s Park lobbying for funding. We didn’t have the capacity to build this water and treatment plant on our own. I was able to get funding to renovate and upgrade the plant to where it is now.

What would you say to Indigenous youth that are interested in community and local politics?

Go for it! Everything I’ve done has always been “just go for it”. I was scared of not having experience, but you have to do it to get experience. If you don’t put yourself out there, you won’t get experience. How can you get experience if you don’t get out of your comfort zone. You won’t be able to learn and grow.

You’re also a Juno award winning musician! Explain what it was like to be an Indigenous musician and win this award?

I won the JUNO award when I was the Mayor of Sioux Lookout. When I first visited some music producers in Nashville, they didn’t like my music. There was one producer who asked for my Cree songs. He said “Wow that’s different, Shania Twain and Garth Brooks aren’t singing this!”. So, I came back to Sioux Lookout and recorded more Cree songs. Later that year I was nominate and won. I didn’t know how things would work out, but I just had to go for it!

How has your Indigenous background influenced or inspired your work?

It’s inspiring to collect stories of our people on the land, water, animals, and insects. I’ve also appreciated using my Indigenous viewpoint on things while working with the scientists and blending those two knowledge bases. My connection of knowing the language and my lived experience while having that connection with the people and takes me back to where I grew up – on the land.

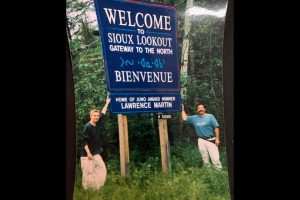

Lawrence with the entrance sign into Sioux Lookout, 1990s

Sol Mamakwa

Sol Mamakwa is a member of the New Democratic Party (NDP) and was elected Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) for Kiiwetinoong in 2018. Prior to becoming an revered Indigenous politician Sol worked for Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) and served on the board of Sioux Lookout First Nations Health Authority (SLFNHA). Born in the Sioux Lookout Zone Hospital and raised in his community, Kingfisher Lake First Nation, Sol continues to speaks the language, engage in traditional activities and live the traditional way of life.

You are the first member of provincial parliament for the new riding of Kiiwetinoong; What led you to run for MPP?

If you would have asked me in the summer of 2017 if I would run for Ontario parliament, I would have laughed at it. Even when Kiiwetinoong was being created, I would have never thought of running. I say that because I ran from the encouragement of people wanting me to run. I decided to run because of the different people that reached out to me – leaders, community members, etc.

The important part was, at that time, I was focused on health policy – health policy at NAN, and when I think of health I think of the reasons why our people, get sicker and sicker. We must be able to talk about the social determinants of health – water, food security, economic development, etc. When I made the decision to run, I wanted a role where I can talk openly about the area and how I can help as their member of provincial parliament.

What are some achievements that you are most proud of during your time as MPP?

Currently I am the only person in the Ontario Legislative that is First Nation. I am proud to be able to speak openly about issues facing the North, to be able to speak on lived experiences in a public way, it is very important to be able to do that. We need to speak about these topics.

Raising awareness of the issues that we, Indigenous people, face in the far North of Ontario – housing, suicide, house fires – I can raise these challenges up on the provincial level. Travelling and speaking with elders, that is moving to me. That is important for me to do.

I got elected in a very difficult time – COVID, moving forward with Truth & Reconciliation. With the heckling that goes back and forth, I am not attacking when I speak on these very serious topics and stories. I have been able to keep up for the past 5 years where the opposition nor the government cannot heckle me, because I am speaking on these important cultural issues.

What would you say to Indigenous youth that are interested in provincial and federal politics?

I think it’s important to understand how legislation and laws are created. It’s important that Indigenous youth get involved not just with federal and provincial politics, but also on a municipal level. There are so many leaders in our First Nation communities and we must follow what’s going on with First Nation politicians and pay attention to what they are saying and speaking on.

There is no small change – write a letter, be involved, there is always something to do. For example, there is no postage to send a letter to my office. Send me a letter and I can help raise your issues on a provincial level.

We need the youth voice, the youth matter. We see youth are going through many mental health issues and they are the only ones to provide that voice to push for change. Sometimes the decisions we make, we don’t know how it impacts the youth, that’s why we need the youth to speak up.

How has your time on the Board of Directors at SLFNHA helped your work now?

I did the switch over in my career in the mid 2000s. Originally, I was the education director for Kingfisher Lake and I moved to Tribal Council on education and did a big switch over to health, it was a learning curve. I had to ask a lot of questions. As the health director at Shibogama I was appointed to the Board of Directors at SLFNHA. Because I was so new at health, I had to ask a lot of questions and learn.

You learn from asking questions – many roles and responsibilities were appointed to me at SLFNHA that I had to learn. They had to have the confidence in me to have the board and governance roles to address numerous issues in health that we were facing in the north. SLFNHA played a huge role in me running for MPP because I understood the provincial and federal side of health care. This is where I started to understand the system for First Nations in terms of provisions of health services. The system appears broken, but when I started to think about it more, the system is not broken, it’s working as it’s designed to do – oppression and colonialism. It is designed that way on purpose. Strategically underfunded with fiscally driven decisions.

What do you see for the future of health care in the north?

I think there should be no wrong approach to health care in the north. My vision is that when you book an appointment, First Nations people can provide our services in our own language and culture all the way through. Cultural sensitivity is key with First Nations persons leading and providing the service all the way through and when you return to your community, and it’s our people providing health services.

Bringing services closer to home – First Nations should have the power to make their own decisions on health care – not federal and provincial governments. We make our own decisions overall and I think once we do that, we can achieve the best health care system in Ontario – not only that, but the best healthcare system in Canada. That’s my hope and vision for healthcare in the north.

Lydia Sherman

Tell us about yourself, where you are from and how did you get started?

My name is Lydia. I live in Sioux Lookout, I’m originally from North Caribou (Weagamow Lake). My husband and I, have three boys. My late dad was a trapper and fisherman. He also ran a small store and later was in a leadership role. My late mom, stayed home and cared for her family in the home.

I’ve worked in the Social/Mental Health field for thirty plus years inclusive, in different capacities. I left twice for short period of time to work in other fields. In Child & Family Services, Court Interpreter, and Indian Residential Support worker.

Knowing the culture and the language was an asset.

In the 1980’s, Mental Health program existed, (and prior to that) through the old Zone Hospital. With few First Nations Mental Health workers working, in the field. As time went on the numbers of Mental Health workers grew.

Workers worked in the old Zone Hospital and travelled out in the field, to the North.

Travelling to the North was required for the workers. Sometimes travelling with psychiatrist, who provided services to the North for Mental Health support and assessments. Assisting them in, interpreting and translating.

Travel had its advantages and disadvantages. Advantage was getting to know the communities and the people. Challenging for me was flying in a small 4 seater plane, no matter what the weather was. No conveniences, like no electricity, no running water. But all was good. But I grew up like that.

My parents reminded me, where I came from and not forget, where I came from.

Three Elders, assisted us in Teaching, Supporting and Guiding in this work, from the culture aspect.

What would you say to new workers in childcare and mental health care?

As the Elders teaching. This is their time, not your time.

Listen. Take time. Be patient.

Advocate when needed, access cultural appropriate services.

Do Self-care, de-brief and Teamwork.

Traumatic events took place within our First Nations peoples. Which resulted and impacted Intergenerational Trauma, in the past, present and the future.

Residential School, Tuberculosis (in the “50’s”) Sixty Scope.

Through my work, I’ve used the tool/model, the “Wholeness Approach.” Involving, the Physical (body), Emotion (feeling), Mind (thoughts-thinking), Spiritual (Belief). Sometimes, these overlap when you help the individual. It’s a process, as the individual walks through this journey.

Sometimes, it’s therapeutic to access nature. Sit by the river, in the quietness of nature, watch the sunset, listen to nature. With the individual who’s reaching out.

How have you seen Nodin grow over the years?

It has grown vastly, in the last thirty years. Providing various Programs and Services to the North. And it has taken positive strides reaching out to the Northern communities, Implementing Services and programs to all ages.

When I was young, my parents encouraged us to go to school and work. And that we would go to school and work with people of all diverse backgrounds. And not to think less of anyone, but respect all. And that we would be working with people of diverse backgrounds.

I feel honoured to have worked in Mental Health field, with colleagues of diverse backgrounds. And to work in different capacities in the helping field.

There’s strength in numbers.

I currently with a FN organization with Mental Health Wellness Team

Randy White

Randy White is an award-winning musician and a Cultural Clinician in Keewatin, Ontario. His Anishinaabe name is Kebeyaasang belong and belongs to the Bizhew (Lynx) clan from the community of Naotkemgwanning (Whitefish Bay) situated on the shores of Lake of the Woods in Treaty 3 territory. Randy holds a Masters degree in counselling Psychology and a member of the Ontario

College of Psychotherapists and is married with two children. Here is his interview with Reece Van Breda, SLFNHA Communications Officer.

You are an award-winning musician with your drum group – how has music contributed to your upbringing?

As most of us may or may not be aware, traditional First Nations song and dance was not widely practiced, especially with young First Nations people during the 40’s on to the 70’s. The community elders of Whitefish Bay seen this, and in order to preserve, reclaim and rejuvenate First Nation song and dance, the elders directed that a drum be created. They invited the young men of the community to begin learning the songs and teachings of the Anishinaabe. From here the Whitefish Bay singers began travelling a path that we continue to this day. As an original singer of the group, I believed that the drum has kept me close to the life of the Anishinaabe during my upbringing. It made me realize the foresight of the elders and their kindness in bringing hope to the future generations.

What are some achievements that you are most proud of?

That we are still doing what we love doing, singing. That people will still listen to. We are continually travelling to other parts of Turtle Island, learning from others and sharing our experiences. Being a part of Pow Wows and ceremonies is such a gratifying way of life.

What would you say to Indigenous youth that are interested in pursuing music?

Whether it be music or another form, having the courage to take those chances is scary for sure but exciting. Sometimes, you may feel dreams are unattainable but if you keep at it you never know how far you can go. Life is exciting if you want it to be.

You currently work as a Cultural Clinician with the Kenora Chiefs Advisory. How can cultural clinicians help to foster reconciliation within the healthcare field?

I try to tread lightly as my experiences may not fit with other First Nation communities. My only suggestion to other clinicians is to continually learn about the First Nations people you work with. To honour their resilience, the people, customs, language and culture. This can be achieved by following the Grandfather Teachings of humility, kindness, and respect.